About Us

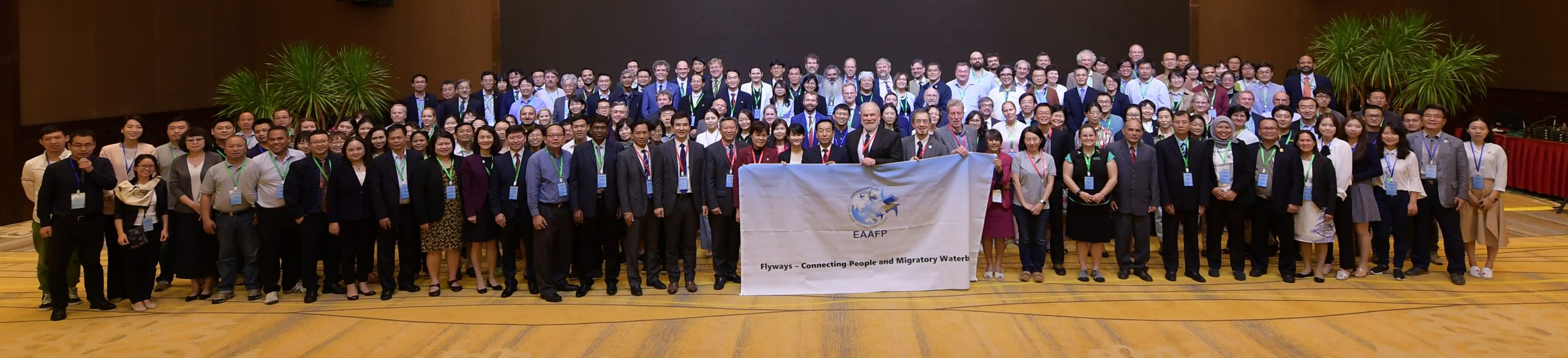

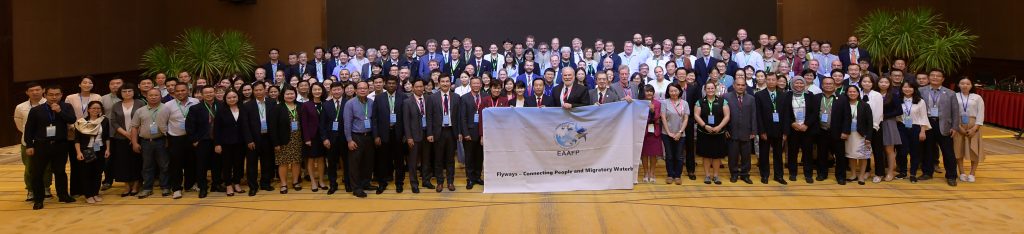

The East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP) was launched on 6 November 2006. It aims to protect migratory waterbirds, their habitats and the livelihoods of people dependent upon them. There are currently 40 Partners including 18 national governments, 6 intergovernmental agencies, 14 international NGOs, 1 international organisation and 1 international private enterprise.

Our Mission

The Partnership provides a flyway wide framework to promote dialogue, cooperation and collaboration between a range of stakeholders to conserve migratory waterbirds and their habitats. Stakeholders include all levels of governments, site managers, technical institutions, UN agencies, development agencies, industrial and private sector, academe, non-government organisations, community groups and local people.

Our Work

EAAFP Partners work together to develop Flyway Site Network to ensure the internationally important wetlands are sustainably managed. It works to enhance research, monitoring, information exchange as well as CEPA (communication, education, participation, awareness) of conservation of migratory waterbirds and their habitats. It enhances capacity building on management and develop flyway-wide conservation approaches.

Connecting people and migratory waterbirds

EAAFP is a Partnership which aims to conserve migratory waterbirds and their habitats, considering both people and biodiversity of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. This 6-minutes video will help you better understand how important it is to protect migratory waterbirds and the wetlands they rely on as well as the work of EAAFP.

EAAFP Flyway Site Network

EAAF Countries

Flyway Site Network

National Governments

EAAFP Partners

EAAFP Key Species, Working Groups and Task Forces

EAAFP Partners

National Governments (18)

Inter-Governmental Organisations (6)

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (2006)

Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar Convention) (2006)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2009)

Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (2013)

Convention on Biological Diversity (2014)

ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity (2014)

International Non-Governmental Organisations (14)

Australasian Wader Studies Group - BirdLife Australia (2006)

International Crane Foundation (2006)

Wetlands International (2006)

World Wildlife Fund (2006)

BirdLife International (2006)

Wild Bird Society of Japan (2007)

Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (2010)

Pukorokoro Miranda Naturalists Trust (2010)

Wildlife Conservation Society (2013)

Hanns Seidel Foundation (2016)

Paulson Institute (2018)

Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (2020)

Mangrove Foundation (2020)

Ramsar Regional Center - East Asia